-40%

CIVIL WAR TREASON/RADICAL COPPERHEAD PA SENATOR PUBLISHER DOCUMENT SIGNED CHECK!

$ 5.27

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

PETER GRAY MEEK(1842 – 1919)

CIVIL WAR RADICAL “COPPERHEAD” POLITICIAN, NEWSPAPER PUBLISHER and EDITOR FROM PENNSYLVANIA -

ARRESTED 5 TIMES BY UNION MILITARY AUTHORITIES

FOR ‘HIGH TREASON’ IN HIS SUPPORT OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA

!

,

OWNER OF THE “

DEMOCRATIC WATCHMAN

” – AN ANTI-LINCOLN PA NEWSPAPER

CONDEMNING UNION WAR EFFORTS,

MEMBER OF THE PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FROM 1868-1872,

&

SENATOR FROM PA 1891-1895.

Meek advocated appeasement of the South and full restoration of the antebellum constitutional order. Meek was a character notable for his fearlessness and radicalism, providing an enlightening look into the undercurrent of a usually hidden political dissent during the Civil War.

This lightning rod of a man brought out the worst in his opponents and showed the underlying animosities and fears that defined anti-war feelings during the Civil War.

<

<>

>

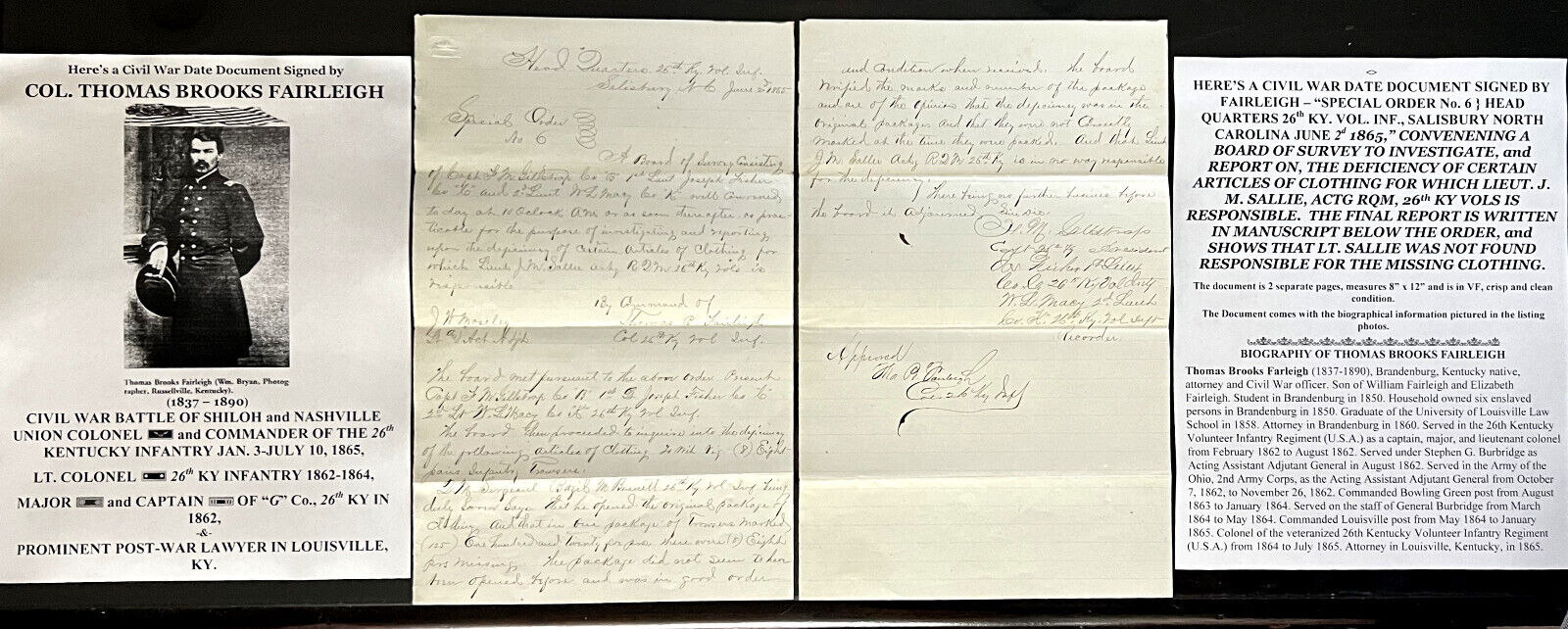

HERE’S AN AUTOGRAPH DOCUMENT SIGNED BY MEEK – A JAN.7,

1900

RECEIPT FOR A SUBSCRIPTION TO THE “

DEMOCRATIC WATCHMAN

”

THE DOCUMENT MEASURES 7” x 3”and IS IN VF CONDITION.

A RARE ADDITION TO YOUR CIVIL WAR PA POLITICAL HISTORY AUTOGRAPH, MANUSCRIPT & EPHEMERA COLLECTION!

<<>>

BIOGRAPHY OF THE HONORABLE P. GRAY MEEK

Peter Gray Meek

, Pennsylvania Politician, Editor and Publisher, was born in Half Moon, Centre County, Pa in 1842, son of Reuben H. Meek and Mary Ann Gray Meek. Meek received a common school education.

In 1861, at the start of the Civil War, Meek purchased the Pennsylvania newspaper called the “Bellefonte Watchman” and made it a leading, influential, and prosperous newspaper.

For expressing his disapproval of the action of government spies and provost marshals who were hounding the people during the war, he was placed under arrest by the military, imprisoned in the political pen at Harrisburg, Pa.,

and afterward discharged “on parole” without trial or a knowledge of the charges, if any, that had been preferred.

He continued to edit and publish the paper from 1861 to 1919, making it a recognized leader among the Democratic papers of the State of Pennsylvania, and an acknowledged power in the formation of Democratic Party policies, as well as in the selection and support of Democratic candidates.

Meek was a member of the Pennsylvania Legislature from 1868 to 1872;

Clerk of the PA House of Representatives in 1883; member of the Senate from 1891-1895; Surveyor of Customs at Philadelphia from 1894 to 1898; Secretary of the Democratic State Committee 1872, 1883, and from 1902 to this time (1911).

He married Susan M. Meek, and they had six children; Rachel, Luella, Mary Gray, Elizabeth Breckenridge, George R. Eloise and Winifred Baron

<<>>

MEEK THE “

COPPERHEAD

”

Until the emergence of

Meek

, the Democratic papers of the area and in the North at large became more muted in their criticism of the Lincoln administration’s handling of the crisis after Fort Sumter. Peter Gray

Meek

’s Democratic Watchman did not hide its desire for an end to hostilities with the South. In a July 18, 1861 editorial he proclaimed that “we are ready for peace now, we long for peace, we pray for peace but the northern people... it appears are not 13ready for it.” Frank Klement, the preeminent historian of the Copperhead movement, has pointed out that for the most part most Democratic spokesmen gave “qualified support” for the actions of the Lincoln Administration during the first year of the war. Unity between the parties defined this point in politics, and “only a handful of recalcitrant Democrats swam against the current,” Klement concluded.

Meek

was certainly one of that small group.

The lack of initial public outcry over the war and the policies of the Lincoln Administration did not necessarily indicate alack of dissent; most critics were driven to silence by the public fervor over the war, making any dissenter liable to public protest, arrest or violent retribution. As well the aggressive prosecution by Republican officials against those who spoke out against the war made it a legal liability to voice dissent.

Meek

’s record reflected this as between the years 1861 and1865 he was arrested five times for publishing articles seen as treasonous by local officials, though he would never be officially tried for any of his “crimes.”

Meek

would however face the consequences for his actions in the streets of Bellefonte. On August 5th1862 he was attacked by a group of “young rowdies.” This incident, according to the Watchman, “threatened to terminate in a general riot, ”though

Meek

would be only“ slightly injured”. The Watchman observed that “the excuse for the attack was the political principles of the Junior [editor], but we apprehend there would have been no difficulty had not the youngsters been urged on by those who were old enough to have known better”; the newspaper, then, was insistent in blaming the attack on

Meek

’s political opponents. It is clear his advocacy of anti-war views in this period was not only brave politically, but put him in personal danger.

Meek

would re-emerge in the summer before the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation having purchased the controlling interests of the Democratic Watchman. Now an owner of the paper,

Meek

no longer had to worry about being pressured by his colleagues to tone down his rhetoric. He quickly returned to the inflammatory style of editorial that had gotten him ousted as junior editor, reflecting the concerns of these newly disillusioned Peace Democrats vowing to “support the government only as a government of white men established for the exclusive benefit of white men: combating the vile heresies of modern abolitionism which seeks to reverse the laws of nature by placing the negro race up on an equality with the white [race].”He blamed abolitionists for the current crisis, and framed the war as one perpetrated to violate the South’s constitutional right to slave ownership.

Meek

’s use of racist rhetoric was in a way ahead of its time, framing the war as one for the abolition of slavery several months before the issuance of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Exploitation of racial fears would be the key factor in the Democratic victories of 1862, and the issuance of the Proclamation would bring it to the forefront of the discourse as many saw their fears of an abolitionist war coming to fruition. As it was still unpopular to condemn the war, the Democratic rallies, conventions and meeting held in Pennsylvania during the 1862 election season emphasized denunciation of secessionists, abolitionists, and arbitrary arrests while pledging loyalty to the Constitution. After the issuance of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, the rhetoric expanded to include exploitation of fears of “black invasion” and racial mixing.

Meek

, in his advocacy of recognition of the Confederacy, showed that he was not as naïve as many Copperhead editors who thought that an end to the prosecution of the war could bring the union back to its former self. He advocated recognition of the Confederacy as he felt the states had a right to secede and he felt recognition was inevitable if Northerners wanted hostilities to eventually end; whether it was “now, or after a few hundred thousand more men are murdered,” acknowledgment of the right of secession in

Meek

’s mind was the only way that the fighting would cease. Papers like the Watchman were no longer alone in their opposition to the war, as war weariness set in in1863 and a number of prominent Democrat papers began switching to an anti-war stance.

Further, the implementation of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1

st

1863made opposition to the Administration more appealing to conservatives, giving credence to the fear of abolitionism that had long been a part of Democratic ideology in the North.

Meek

held abolitionism accountable for the onset of war, even going so far as declaring it to be “

the Sole cause of secession and the present inhuman civil war,

” which was being waged now to “turn loose upon the country 3,000,000 negro servants which are property of the South, their title to which is as good and Constitutional as ours to our horses.”

In the summer of 1863,

Meek

was drafted—and his decision to pay the 0 commutation fee and not serve helped to further expose his divergence from the families of soldiers in Bellefonte. He wrote in a subsequent editorial that he bemoaned the fate of the sixty men drafted from Centre County who were forced to risk their lives “on the altar of fanaticism and folly.” Later when the commutation fee was to be removed as an option for draftees,

Meek

advocated resistance to the draft as the only viable option for those opposed to the war.

Meek

placed the responsibility for the anarchy that would inevitably ensue squarely on the shoulders of President Abraham Lincoln.

Meek

was pulling out all stops to get out the vote for George McClellan as well as support behind the Copperhead platform of the Democratic national convention; given the narrow victory that Lincoln supporter Governor Andrew Curtin received in the gubernatorial race of 1863he likely thought there was a good chance Lincoln could lose Pennsylvania.

Desperation showed in the pages of the Democratic Watchman on the eve of Lincoln’s 1864 re-election. Restoration of the Union,

Meek

opined, would be possible only if Lincoln was defeated in November. Despite the Confederacy’s professed desire for continued independence, he promised his readers that if they voted Democratic, “

Lincolnism, niggerism and abolitionism can and will be consigned to political disgrace and the constitution and union saved to us and our children

.”

Despite the results of the election and the seeming imminence of the end of the Confederacy,

Meek

continued to oppose the war, refusing to acknowledge even the possibility of peace or military victories under the current administration.

With the surrender of General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox on April 9th1865

Meek

did not expect an end to hostilities, refusing to acknowledge it as any kind of victory at all: “the capture of Richmond is simply the capture of one of our own cities; the surrender of Lee is simply the surrender of one American to another; the subjugation of the South is simply the subjugation of part of our own people; the destruction of their country is simply the destruction of part of our own territory. What is there to cause joy in the accomplishment of these things?”

With Lincoln’s assassination a few days later

Meek

continued with this attitude, publishing editorials that were cold and unfeeling. While lauding the President for his handling of the government since Lee’s surrender, especially when it came to his lenient proposals for conciliation with the South, he refers to the assassination as a tragedy because Lincoln was “just at the beginning of his good acts.” The assassination was not a matter for despair,

Meek

argued, as Lincoln’s Democrat successor would likely continue in the spirit of conciliation. He did err on the side of caution, stating that “if the new President proves to be less of a statesman than the one lately deceased, Heaven help us as a people. His administration, until very recently was full of evil; that the new one will be more so, we cannot, we dare not believe.” The editorial was not taken well, his argument that Lincoln’s death was a tragedy only because he had just recently become competent seemed to people as being disrespectful to the late President.

Despite public outcry against his editorials,

Meek

refused to apologize for his unkind words, standing strong in his conviction that the Lincoln Administration had butchered the rights of the American people and continuing to advocate their reinstatement.

Meek

’s inability to apologize for his editorials on Lincoln’s death was likely what led to his final arrest in early May of 1865. He was arrested by an army sergeant for “counseling resistance to the draft” and was transported to a crowded Harrisburg jail cell. The peculiar sight of the 90 pound

Meek

being led through the streets of Bellefonte by armed soldiers on the way to the train station created quite the spectacle. The sidewalks were lined with spectators. Not surprisingly, these residents of downtown Bellefonte were there to show their support for his arrest, though some supporters of

Meek

did accompany the crowd.

He would later be brought up on charges for his Lincoln remarks, though a trial never occurred. On May 25,1865

Meek

returned from an appearance before Pittsburgh’s U.S. District Court, where he plead not guilty to charges of printing treasonable material related to his editorial on the assassination. On his return, as he made his way from the train station to the offices of the Democratic Watchman on South Allegheny Street, “some bystanders cheered; some jeered as

Meek

smiled and doffed his hat to all that passed.”When he arrived at the offices of the Watchman he made a dramatic bow to passersby and entered.

Following the end of the war,

Meek

continued his resistance to the Republican-controlled government; with the passage of the 14thAmendment through both houses of Congress on June 13,1866

Meek

responded with a call to violent resistance: “when despotism denies freedmen the ballot they have one resource left—THE BAYONET. Between this and negro EQUALITY, you, with men of the North MUST CHOOSE. Call your meeting, let those in authority know your wishes, and if they are not heeded, be ready to stand by your rights and your race. ORGANIZE! ENROLL! EQUIP!”

Meek

was elected to the Pennsylvania State House of Representatives in 1867, and made an impassioned speech in that body against the 15

th

Amendment while it was up for debate. He continued to be a representative of the area throughout the rest of the 19

th

century, fighting for the Democratic principles he expressed within his paper whilst remaining editor of the Watchman until his death in 1919. He would also be a key figure early in the development of the Pennsylvania State University, always working as representative of the institution in the state legislature, fighting for funding and expansion.

Sources:

“Distinguished Successful Americans of Our Day: Containing Biographies of Prominent Americans Now Living…”1912

“Copperhead in Our Midst; Peter Gray Meek and His Peculiar Place in Bellefonte Politics During the Civil War” by Jeffrey Glossner

I am a proud member of the Universal Autograph Collectors Club (UACC), The Ephemera Society of America, the Manuscript Society and the American Political Items Collectors (APIC) (member name: John Lissandrello). I subscribe to each organizations' code of ethics and authenticity is guaranteed. ~Providing quality service and historical memorabilia online for over twenty years.~

WE ONLY SELL GENUINE ITEMS, i.e., NO REPRODUCTIONS, FAKES OR COPIES!